|

Home

Page 1/6 (this page)

Page 2/6

Page 3/6

Page 4/6

Page 5/6

Page 6/6

|

El Hierro, the youngest Canary.

Island of landslides

webpage 1/6

Text: Annemieke van Roekel, geoscience journalist

www.vuurberg.nl.

This article was first published in Gea Magazine (September 2022).

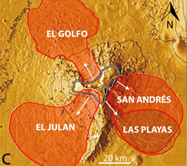

El Hierro, the most southwestern island of the Canary Archipelago, is covered with many cinder

cones and other young volcanic sediments. Its distinct three-armed island structure is determined

by the structure of rift zones

combined with the collapse of the flanks of the three ridges.

Recent volcanism has made it a beautiful Geopark, with extensive areas of malpaís,

rope lava and cinder cones covered by the Canary Island pine (Pinus canariensis).

El Hierro is the top of a volcanic structure that rises 5.5 km from the Atlantic Ocean floor and

rises 1.5 km above water. What we see is just the tip of the iceberg. As a result of

major landslides, extensive debris fans (aprons) lie all around the island (Fig. 1), with an estimated volume

of three times the current section above sea level.

Fig. 1. Debris avalanche deposits on the sea-floor, as a result of lateral collapses off the flanks.

Carracedo & Troll, 2016 (fig. 2.9C). With kind permission.

El Golfo

The last landslide in the Canary Islands was about 15,000 years ago, possibly below sea level,

at El Golfo, in northwestern El Hierro (Masson 1996).

But the first major landslide in El Golfo occurred much earlier,

probably around 130,000 years ago, when the northern ridge collapsed.

Both landslides occurred during a period with sea levels one hundred meters lower than today,

during an ice age.

Since its subaerial existence, 1.12 million years ago, four major landslides

have occurred on El Hierro, and these have largely determined the three-armed shape

of the island. Intrusions of dikes have contributed to the instability

of the flanks (Carracedo et al., 2016). The three-armed geometry is also the basic structure of La Palma

and Tenerife, but on El Hierro the shape is more pronounced due to the young age of the island and

the collapse of the flanks on all three sides.

It wasn't until 1972 that Hausen interpreted the 'crater' of El Golfo (Fig. 2)

as the result of a mega-landslide, at that time without the knowledge

of submarine debris fans. Before then, people thought of a real crater created by a

volcanic eruption, succeeding the theory of fluvial erosion.

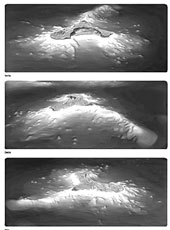

Modern techniques with sonar data (Fig. 3) of offshore areas, and to a lesser extent

seismicity, provided definitive evidence of large-scale prehistoric landslides on El

Hierro and the other islands. Of all four major landslides on El Hierro, that of El Golfo is

the most visible and accessible.

Fig. 2 (left). El Golfo 'crater' (Frontera), with Roques de Salmor at the horizon. The tiny rock are famous

for the (extinct) Hierro Giant Lizard. Fig. 3 (right). Bathymetry mapped

with sonar from three directions: north (top), west (center) and south (bottom). Seabed data

are important to reconstruct and date landslides. Avalanche deposits from El Golfo

have been observed up to 65 km from the coast. Image: CIMA / Instituto Español de Oceanografía.

Page 1/6

Page 2/6

Page 3/6

Page 4/6

Page 5/6

Page 6/6

Copyright: Annemieke van Roekel

Last update: 28 December, 2022

|